Lessons Learned From The Flint Water Crisis

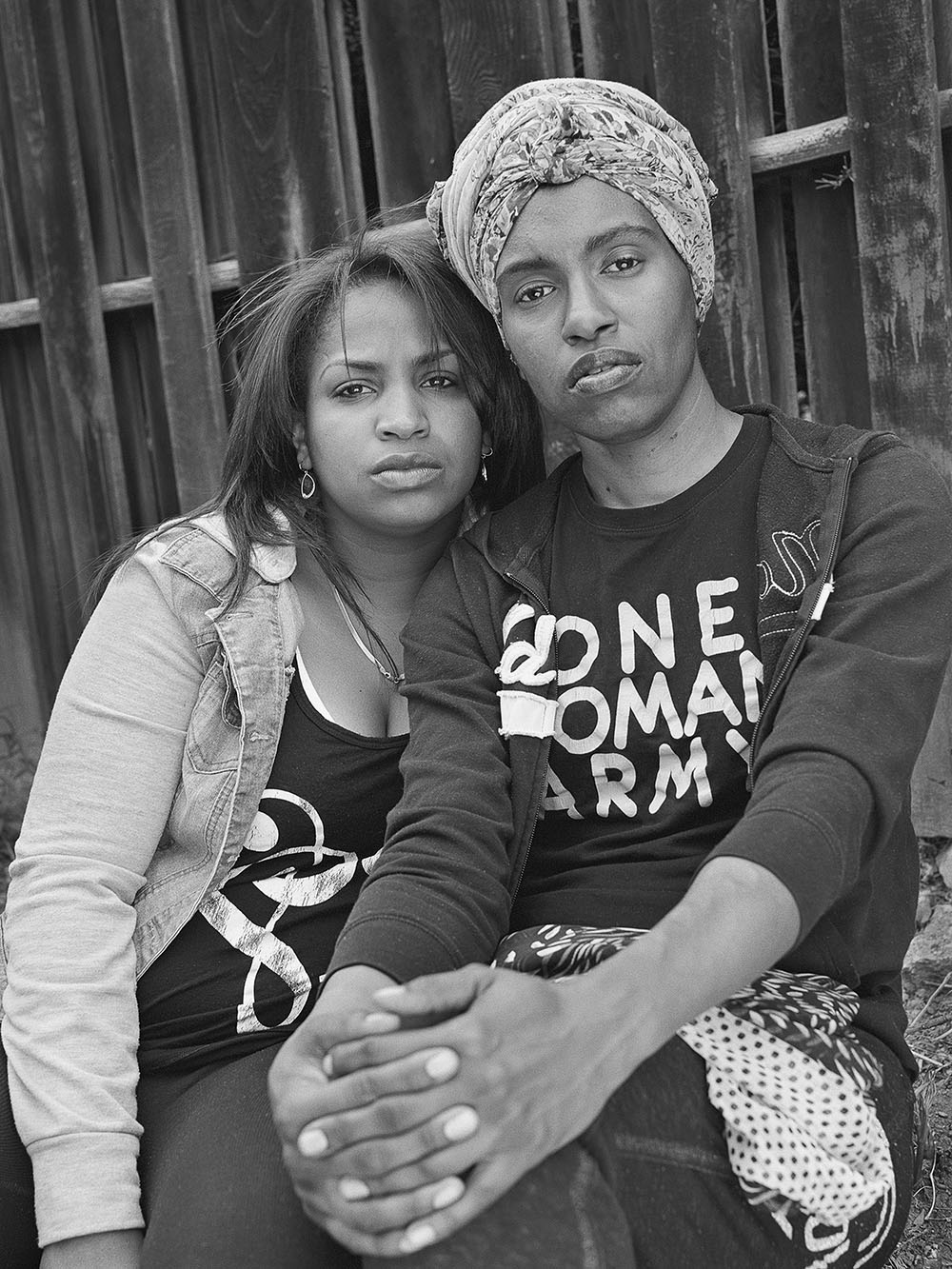

Sometimes it takes more than a village – sometimes it also takes the help of an artist – to right a serious environmental injustice. In 2016, renowned artist LaToya Ruby Frazier set out to create a photo essay about the Flint, MI drinking water crisis, widely regarded as one of the U.S.’s most devastating ecological disasters. She found able collaborators in Shea Cobb and Amber Hasan – poets, activists, mothers and best friends. Cobb and Hasan helped Frazier embed herself in Flint, introducing Frazier to their families and “The Sister Tour” collective women artists created in response to the crisis.

Shea with Her Best Friend, Amber Hasan, Shea’s Manager, Poet, Writer, Hip-Hop Artist, Actor, Comedian, Herbalist, Activist, Community Organizer, and Business Owner of Mama’s Helping Hands, Flint, Michigan I, 2016-2017. ©2022 LaToya Ruby Frazier. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

The crisis came to a head in April 2014 when a nonelected, Governor-appointed emergency city manager led the City through a series of fateful decisions. To cut costs, the City stopped purchasing drinking water from Detroit (which sourced water from Lake Huron). Instead, the City began drawing drinking water from the Flint River. And even though the river had been highly contaminated by years of industrial and municipal waste discharges, the City discontinued anti-corrosion treatment. City water soon corroded service lines to over 50,000 homes, allowing bacteria and lead to leach into tap water.

Almost immediately, residents reported discolored water, foul odors, and skin rashes. Officials insisted the water was safe, but problems continued to mount. Water mains broke at unusually high rates. General Motors, itself a long-term discharger to the Flint River, complained that City water corroded newly machined engine parts and switched its engine plant to another supplier. Chemical and bacteria levels in the water rose, causing serious health effects. At least 12 people died and 90 were sickened with Legionnaire’s disease. Nearly 10,000 children were poisoned by exposure to extraordinarily high levels of lead.

In 2015, the City reconnected to the Detroit water system and, the following year, began replacing residential lead service lines, a process it proposed to complete this Fall. Meanwhile, residents awaiting pipe replacements had to drink, cook, and bathe with bottled water.

As the crisis dragged on, a retired veteran, Moses West, offered help. West had invented an energy efficient atmospheric water generator capable of pulling ambient air through a high volume filter and mechanically collecting the resulting water condensation. The generator, which West offered to bring to Flint, could produce roughly 2,000 gallons of clean water per day.

But Flint residents lacked funding to move the 26,000-pound generator from its Texas base to Flint. Stepping into the void, Frazier used her own funds, along with a generous grant from the Rauschenberg Foundation, to finance the move. Once installed, the generator offered residents awaiting replacement of water lines – or distrustful of the city’s remediation efforts – a temporary but readily accessible source of free, clean water.

Shea and Her Daughter, Zion, Sipping Water from Their Freshwater Spring, Newton Mississippi, 2017-2019. ©2022 LaToya Ruby Frazier. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

By focusing on residents, their strengths and their faith in each other, Frazier managed to wrest from this deplorable history a story of hope, resilience, and community solidarity. Her work demonstrates that the lessons from Flint merit serious study.

Inspired by that challenge, Stamps Gallery, University of Michigan, initiated a partnership with Flint Institute of Arts and Michigan State University Broad Art Museum to create a landmark exhibition drawn from Frazier’s 5-year body of work. Entitled Flint Is Family In Three Acts, the exhibition takes place concurrently at all 3 museums, each of which features a different phase of the story. Act I (2016-2017) at the Flint Institute of Arts introduces Cobb, Hasan, and The Sister Tour collective. Act II (2017-2019) at the MSU Broad Art Museum follows Cobb as she migrates to Mississippi and returns to Flint, searching for a healthy environment and supportive school system for her daughter. Act III (2019-2020) at the Stamps Gallery shows how Frazier’s photography and West’s ingenuity provided much welcomed support to the long-suffering community.

Moses West Holding a “Free Water” Sign on North Saginaw Street Between East Marengo Avenue and East Pulaski Avenue, Flint, Michigan, 2019. ©2022 LaToya Ruby Frazier. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

The museums aim to deepen our understanding of how we can more effectively foster environmental justice in economically strapped communities and to highlight the artist’s role as an agent for effecting positive social change.

The exhibitions could not be more timely. They bear on our response to three urgent challenges:

- Climate change: The conditions which led to the Flint crisis are not unique. Much of the aging U.S. water infrastructure needs replacement or major upgrading. Climate change will further strain water delivery systems. Extreme floods will wash massive amounts of additional pollutants into waterways. Extended droughts will reduce river flow, increasing competition – and costs – for fresh water. Our newly enacted infrastructure law and other appropriations contain $15 billion for replacing lead pipes. We must spend this money promptly and wisely to strengthen municipal resilience.

- Equity: Former Director of EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice Barry Hill summed up Flint’s challenge in the American Bar Association Human Rights Magazine: “Flint is a majority poor Black city disproportionately exposed to environmental harms and risks as a result of the disposal practices of the auto industry over decades.” Governor Snyder’s nonpartisan Flint Water Advisory Task Force also acknowledged: Flint residents “did not enjoy the same degree of protection from environmental hazards as that provided to other communities.” How can we change existing legal structures to ensure safe drinking water for all?

- Harnessing the power of art to meet today’s needs: Frazier played a critical role in Flint, amplifying residents’ voices, ensuring their woes were not forgotten, challenging the world outside Flint to empathize with, learn from, and respond to its suffering. Increasingly in our climate-challenged world, artists are asking: how can I help my community heal from devastation caused by extreme weather? Frazier deftly modeled a potential response – these exhibitions help us learn from her.