Contributing Artist Patricia Johanson Designs Visionary Infrastructure

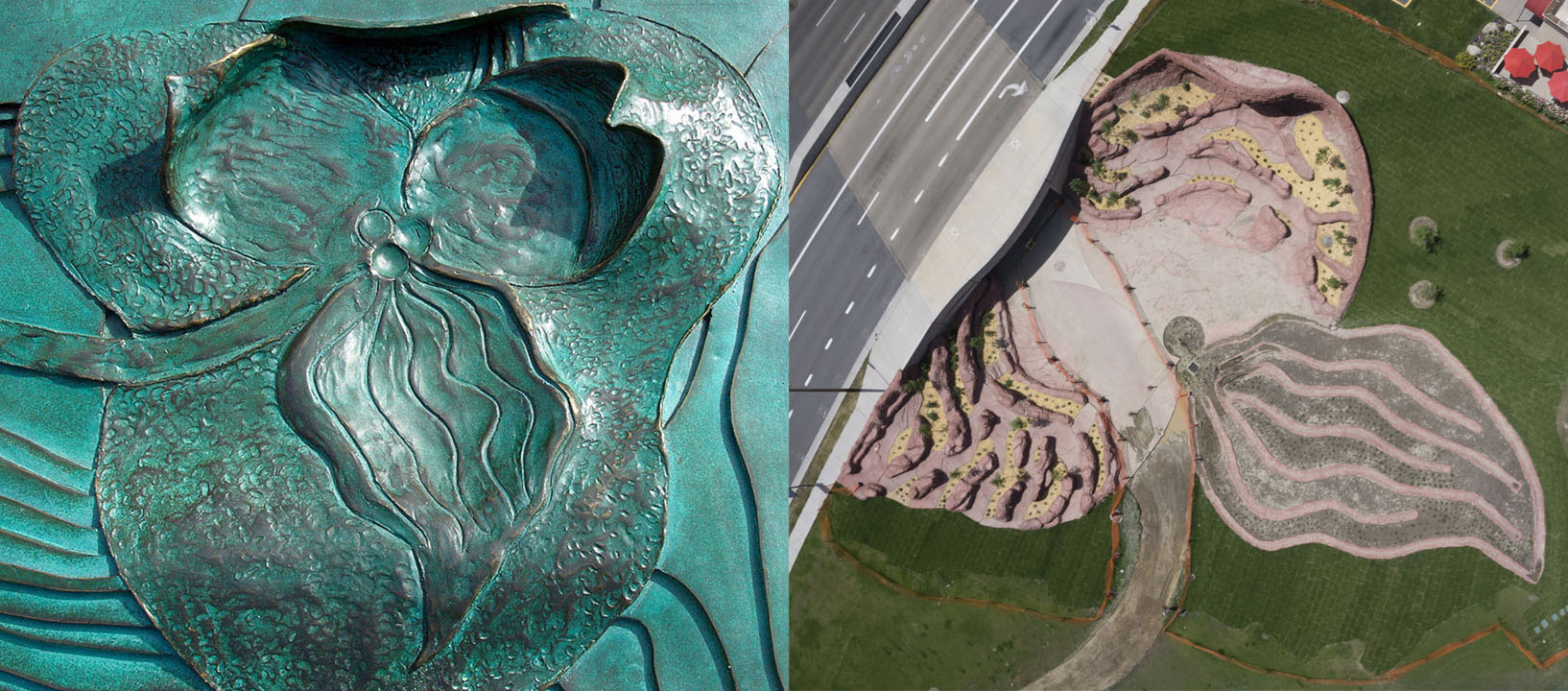

Patricia Johanson’s Sego Lily Dam in Salt Lake City, Utah may well be the world’s first flood control project that doubles as a work of art. Designed in the shape of a sego lily, Utah’s state flower, the dam allows floodwater to pool in the flower’s “bowl” (with its 30-foot high walls), then flow by gravity down the lily’s “stem,” under an 8-lane highway and into a nearby creek. Plants and wildlife perches grace the sculpture’s walls.

During dry spells, the dam serves as a community park, where pedestrians and wildlife can share space within the city. When huge volumes of rain and snowmelt descend from the nearby Wasatch Mountains, the dam – designed to absorb a 10,000-year storm – prevents life-threatening floods.

The project honors local history too. The sego lily is a powerful symbol: early Mormon settlers ate the lily’s bulbs to avoid starvation. And the sculpture portrays landscapes significant to early Mormon pioneers – the maze of snow-clad peaks traversed by settlers and the irrigation ditches they dug to nourish crops.

The project also respects the area’s natural history – and attempts to heal the ecological damage we’ve inflicted. For example, by reconnecting natural areas on opposite sides of the highway, the project restores a wildlife connection that had been lost to urban development.

Patricia Johanson, Model for the Sego Lily Dam (left) and aerial photo of the constructed dam (right). ©Patricia Johanson, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

This project is the latest to be completed in Johanson’s career-long effort to transform the way we approach civil engineering. For the past century, the Bureau of Reclamation and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers have built numerous public works projects – dams, reservoirs, irrigation canals, pipelines, tunnels, pumping and hydroelectric plants and river modifications – to make water flow as humans demand. In hindsight, this constrictive engineering often solved one problem by creating another, destroying living ecosystems and sacred sites in its wake. Indeed, today’s public works projects sometimes involve the removal of earlier structures.

Johanson offers planners and engineers an alternative vision: building multi-functional projects, which collaborate with, rather than control, nature. “The future of all water should be local recycling within the context of living landscapes,” she advises. She maintains that we can absorb floodwater, minimize erosion, and sustain water supply – and simultaneously lessen pollutants, enhance biodiversity and beautify our surroundings – when we allow infrastructure to serve as territory for both people and animals.

We previously reported on one of the earliest of Johanson’s inventive designs to be constructed: a municipal flood basin for Dallas’ “Fair Park Lagoon,” completed in 1986. The Sego Lily Dam is yet another brilliant advancement on integrating nature and civil engineering through art.

Johanson’s philosophy is as straightforward as it is visionary. “The boundaries between human beings and nature are porous,” she explains. “By incorporating functional infrastructure within the living world, engineering can become more resilient, inclusive, and continuously creative, harnessing and preserving the biological processes on which we all depend.”

“Framing infrastructure within a cultural, visual, and historical context also empowers ordinary people to engage more readily with serious underlying environmental issues,” she adds. Reactions to her latest project confirm the cultural impact of her approach: Salt Lake City Public Schools have incorporated this project in their environmental lesson plans and the sego lily image has sparked restorations of this threatened plant throughout Utah.

Click here for a short video to see the Sego Lily Dam and learn how it connects to nearby natural areas like Parley’s Creek and Sugar House Park.