Xavier Cortada is the University of Miami Department of Art and Art History’s Professor of Practice. He is also an internationally acclaimed environmental artist, whose work has been shown across five continents and is in the permanent collection of the World Bank.

He has just won the prestigious 2021 National Wetlands Award.

Administered by the Environmental Law Institute (ELI), the Award is supported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Natural Resources Conservation Service. Awardees are recognized for their individual achievements in one of five categories: Promoting Awareness, Local Stewardship, Wetlands Program Development, Wetlands Business Leadership, and Youth Leadership. Cortada won for “Promoting Awareness” of the importance of mangroves to coastal ecosystems.

“The recipients of the National Wetlands Awards are on the forefront of protecting wetland resources in the face of development and climate impacts,” said ELI President Scott Fulton. “Through their dedication and achievements – even in the midst of a pandemic – they inspire wetlands protection across the country and worldwide. After the tumultuous year we’ve experienced, I welcome and celebrate the optimism, energy, and hope these individuals bring forth through their work.”

For fifteen years, Cortada has creatively harnessed the power of art to motivate Miami-Dade County residents to learn about, conserve and restore mangrove wetlands. Commissioned in 2004 to paint 56 columns of the I-95 underpass in downtown Miami, Cortada supervised 800 volunteers in “reforesting” the city metaphorically, painting mangroves on the concrete columns. That experience led him to conceive of a community art project that would actually reforest the built environment.

Beginning in 2006, Cortada designed, staffed and led three successive, interrelated, highly innovative and ongoing community art projects to mobilize Miami-Dade residents to care for and restore mangroves:

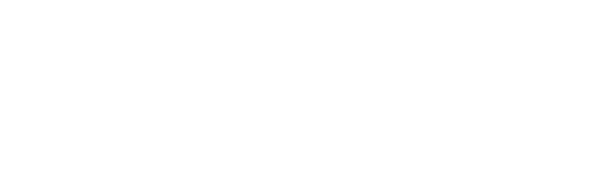

Reclamation Project: Replanting Mature Propagules. ©2021 Xavier Cortada. Photo courtesy of the artist

I. The Reclamation Project (2006-present)

The Reclamation Project educates and engages the Miami-Dade community in restoring mangrove habitats.

A Daunting Goal

Cortada launched the Reclamation Project in the City of Miami Beach in 2006. His ambitious goal: to transform Miami-Dade from an urbanized, increasingly distanced-from-nature population to a cohesive community embracing environmental stewardship of native wetlands.

To succeed, Cortada needed to persuade fellow residents to envision both an entirely different, sustainable ecosystem and a new civic role for themselves. No longer could residents linger outside the problem-solving calculus. Instead, they needed to become active – part of a creative, communal force driving solutions to environmental challenges.

But a community never exists in a vacuum: it is inextricably tied to larger political and regional entities. So Cortada knew he would need to reach beyond Miami-Dade County – to the 7-county Southeast Florida region, and, more broadly, to state, federal, and international audiences. And, lacking any budget for the project, Cortada would have to accomplish his goal as a volunteer and entirely through volunteers.

A Snapshot of the Miami-Dade County Community

Miami-Dade County residents are 65% Latino and 83.8% people of color. In 2010, 51% were foreign born; 93% of whom came from Latin America. Unemployment is high, as is income inequality, poverty, and working poverty. The Southeast Florida region in which it is situated ranked 1st among the largest 150 metropolitan areas in housing burden (defined as spending more than 30% of income on housing.) Blacks and Hispanics had the highest housing burdens, according to An Equity Profile of the Southeast Florida Region.

A Unique Leadership Approach

Cortada used an innovative “learn together” approach modeled on how an artist’s studio works: the artist provides design and methods and studio assistants carry out the project, adding their own innovative ideas on how best to execute the design. Cortada believed that a “learning together” collaboration was more likely to generate a sense of urgency and project ownership – and a more effective design.

Reclamation Project: Propagule Grid In Museum Setting. ©2021 Xavier Cortada. Photo courtesy of the artist.

A Creative Project Design

From the start, Cortada took a two-pronged approach, rooted in “art in the service of science.” He began with education, installing 252 red mangrove seedlings in clear, water-filled cups on a glass wall in Miami Beach’s contemporary art museum, the Bass. This installation, along with two videos documenting mangrove forest destruction, comprised a near month-long exhibition designed to remind residents what Miami Beach was like “before all the concrete was poured.”

Next, Cortada initiated an interactive “ecological art” project to engage residents in restoring mangrove habitat. As the occasion for launching this project phase, Cortada chose Art Basel, an annual Miami Beach art fair drawing ever-larger international audiences (from 30,000 visitors in 2002 to over 80,000 in 2019). He recruited and, with assistance from Key Biscayne Community School PTA President Jacqueline Kellogg, trained over 150 residents as “eco-emissaries” to explain the project to, and enlist support from, Miami Beach restaurants and stores.

Annually from 2006 – 2012, dozens of Cortada’s volunteers collected and installed artistically arranged grids of mangrove propagules in water-filled cups in the street-facing commercial windows along the city’s major pedestrian thoroughfares, such as Lincoln Road, South Florida’s premier outdoor shopping, dining, and entertainment destination. The artistic arrangements of odd-looking vegetation were designed to attract attention – and they did! Passers-by, intrigued by the displays, asked store managers for more information – or read the accompanying educational signage about mangroves.

Once the propagules had matured (about 6-8 weeks after installation), Cortada recruited dozens of volunteers to help replant them. To ensure the propagules thrived in their new location, Cortada solicited assistance from marine biologist Gary Milano, Habitat Restoration Director for Miami-Dade County’s Department of Environmental Resources Management. Milano became the project’s primary science advisor, helping to select appropriate replanting locations until his retirement in 2013. Replanting sites were selected for both ecological and educational value.

Propagule Installation In A Lincoln Road Shop Window. ©2021 Xavier Cortada. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The Frost Science Museum became a partner in the project in 2007, beginning with a 1,111 propagule art exhibition similar to that of the Bass Museum. The Frost Science Museum also recruited project volunteers, eventually creating its own volunteer-based habitat restoration program, Museum Volunteers for the Environment (MUVE), in 2013 and expanding its scope to include replanting of freshwater wetlands, dune habitat and coastal hardwood hammocks in addition to mangroves.

An Enduring Legacy

To date, the project has engaged over 10,000 volunteer participants who collected, learned and taught about or grew mangroves and helped restore 25 acres of coastal habitat. It has:

- trained hundreds of teachers through Professional Development workshops,

- educated tens of thousands of students who either participated in the project or witnessed their peers collect, install, or plant mangrove propagules,

- taught roughly 200,000 Miami Beach visitors annually why mangroves are important to Florida’s coastlines,

- been the subject of professional presentations to numerous organizations, conferences, and museums, including a keynote address at the Florida Art Education Association annual conference,

- been replicated (with regionally appropriate species) at multiple locations: red mangrove propagules in Stuart, FL, vegetable seeds in CA, Atlantic white cedar saplings in NY, and wildflowers in Taiwan,

- spawned mangrove art exhibitions (similar to the Bass’s and the Frost’s) at Florida International University, University of Miami, every Miami-Dade College campus, and locations as far flung as New York City, Auburn, Alabama, and Washington, DC, among others.

But these numbers – impressive as they are – tell only a fraction of the story. As Cortada explains,

“The importance of the project wasn’t how many mangroves we planted, or how many people participated, or even how many people witnessed the project (although our numbers were astronomical). That’s the easy part – and easily outsourced. The more difficult job is to change society’s perspective and sense of responsibility. That’s what the Reclamation Project set out to do.”

Evidence of the Reclamation Project’s efficacy in initiating cultural transformation is strong and growing:

- The project continues to have a vibrant existence across many community platforms.

- The Frost Science Museum made habitat restoration a central part of its educational mission, launching both a popular volunteer habitat restoration program and a countywide in-school mangrove educational program.

- County libraries and public schools – and some parochial and private schools too – have embraced mangrove restorations as a key part of their curriculum.

- Compared to residents of other counties, Miami-Dade adults are significantly more likely to acknowledge that global warming will harm them – and that local officials need to do more to address global warming, according to the Yale Program on Climate Communication.

- The project’s success laid the foundation for two successive Cortada-led initiatives on mangrove preservation (described below).

Plan(T) Educators Engage Community Members At The Pinecrest Gardens Farmers’ Market. ©2021 Xavier Cortada. Photo courtesy of the artist.

II. Plan(T) (2019-present)

Plan(T) educates and engages the Miami-Dade community in harnessing the power of mangroves to protect coastal areas from climate change and associated sea level rise.

While the Reclamation Project focuses on restoring past damage to mangroves, Plan(T) concentrates on preparing for Miami-Dade’s future. As climate warms, sea levels are rising – and likely to continue rising to levels which will drown Miami-Dade’s existing mangrove forests. In addition, past rerouting of the state’s natural flow of water has diminished freshwater flow to the Everglades, making South Florida wetlands more susceptible to saltwater intrusion from rising seas. And drier wetlands make the soil above the limestone rock less resilient, causing mangroves to collapse more readily. Without remedial action, saltwater intrusion into the county’s drinking water, septic tanks, landscape and agriculture is inevitable.

Plan(T) aims to ensure Miami-Dade residents understand this – and do something about it. As before, Cortada began with education. During Art Basel 2019, he installed a mangrove grid exhibition at Pinecrest Gardens’ Hibiscus Gallery, in collaboration with a growing cadre of community institutions: the University of Miami Abess Center for Ecosystem Science and Policy, Pinecrest Gardens, Miami-Dade Public Library System, Miami-Dade Office of Resiliency and the Frost Science Museum. Cortada launched similar exhibitions at all 50 Miami-Dade Public Library System branches, 25 local schools and along Lincoln Road.

The grid formation served two purposes: it turned a collection of propagules into a museum-worthy work of art, tapping art’s power to move hearts as well as minds. And, by creating an artificial mangrove nursery, the grid underscored that, in today’s built environment, mangroves need human help to survive.

Along with education, Plan(T) also spurred community action. The vertical mangrove nurseries encouraged residents to take a free propagule and plant it in their yard alongside a flag indicating the property’s elevation above sea level. The “mangrove in every yard” campaign was intended to stimulate neighbors’ curiosity and spark neighbor-to-neighbor conversations about climate change. And, while the trees sequestered carbon dioxide as they grew, they also helped lay the foundation for the native tree canopy of the future.

To ensure the seedlings’ survival, Plan(T)’s online resource page introduces the public to mangroves, describes the ecosystem services they provide and the threats they face, explains why it is important to plant mangroves in South Florida, and outlines how to plant and care for mangroves.

The project relied upon assistance and advice from an esteemed group of Science Advisors:

- Brian Haus, Chair and Professor, of Ocean Sciences – UM Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science (“UMRSMAS”)

- Sam Purkis, Chair and Professor, Dept. of Marine Sciences, UMRSMAS

- Rafael Araujo, Marine Ecologist, UMRSMAS

- Harvey Bernstein, Horticulturist, Pinecrest Gardens

- Jennifer Possley, South Florida Conservation Manager, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden

Progress to date: Plan(T) has had a strong presence in the community:

- Over 4,000 residents have taken a propagule to plant in their yard.

- Over 500 homes have displayed an elevation flag showing elevation about sea level rise.

- Project presentations have been made at 45 county public libraries.

- Fifteen public schools are participating in the project.

- At 30 weekly Pinecrest Gardens Farmers’ Markets (pre-COVID), tables have been staffed with educational materials and trained volunteer “eco-emissaries” to engage visitors in discussions about the importance of mangroves to the county’s future. Tables were discontinued during the pandemic due to COVID, but the project just recently resumed operations.

Underwater HOA Marker In Front Of Cortada’s Studio In Pinecrest Gardens. ©2021 Xavier Cortada. Photo courtesy of the artist.

III. Underwater Homeowner’s Association (2018-present)

Underwater Homeowner’s Association (2018-present), alerts Floridians to the challenge of sea level rise and provides a forum for community discussion of potential solutions.

Underwater Homeowner’s Association (UHOA) began with Cortada’s goal of alerting residents to the threat of climate change by “making the invisible visible.” Cortada enlisted support from the Village of Pinecrest to encourage residents to install a “marker” in their front yard. The marker is a yard sign openly depicting the house’s current elevation about sea level rise.

The signs are similar in size to the 18” x 24” signs realtors use to sell houses – highly visible and very eye-catching. The backdrop of each sign is a replica of a watercolor painting Cortada had created from Antarctic ice and sediment while stationed in Antarctic as a National Science Foundation Antarctic Artists and Writers Program fellow. Cortada chose this backdrop to emphasize the connection between melting polar ice packs and Florida’s rising sea levels. He also numbered each sign from 0’ to 17’, the land elevation for the 6,000 houses in Pinecrest, and taught residents how to find their home elevation on an online app, Eyes on the Rise.

The yard signs were designed to catalyze conversations among neighbors. Cortada explained, “Block by block, house by house, neighbor by neighbor, I want to make the future impact of sea level rise something no longer possible to ignore.”

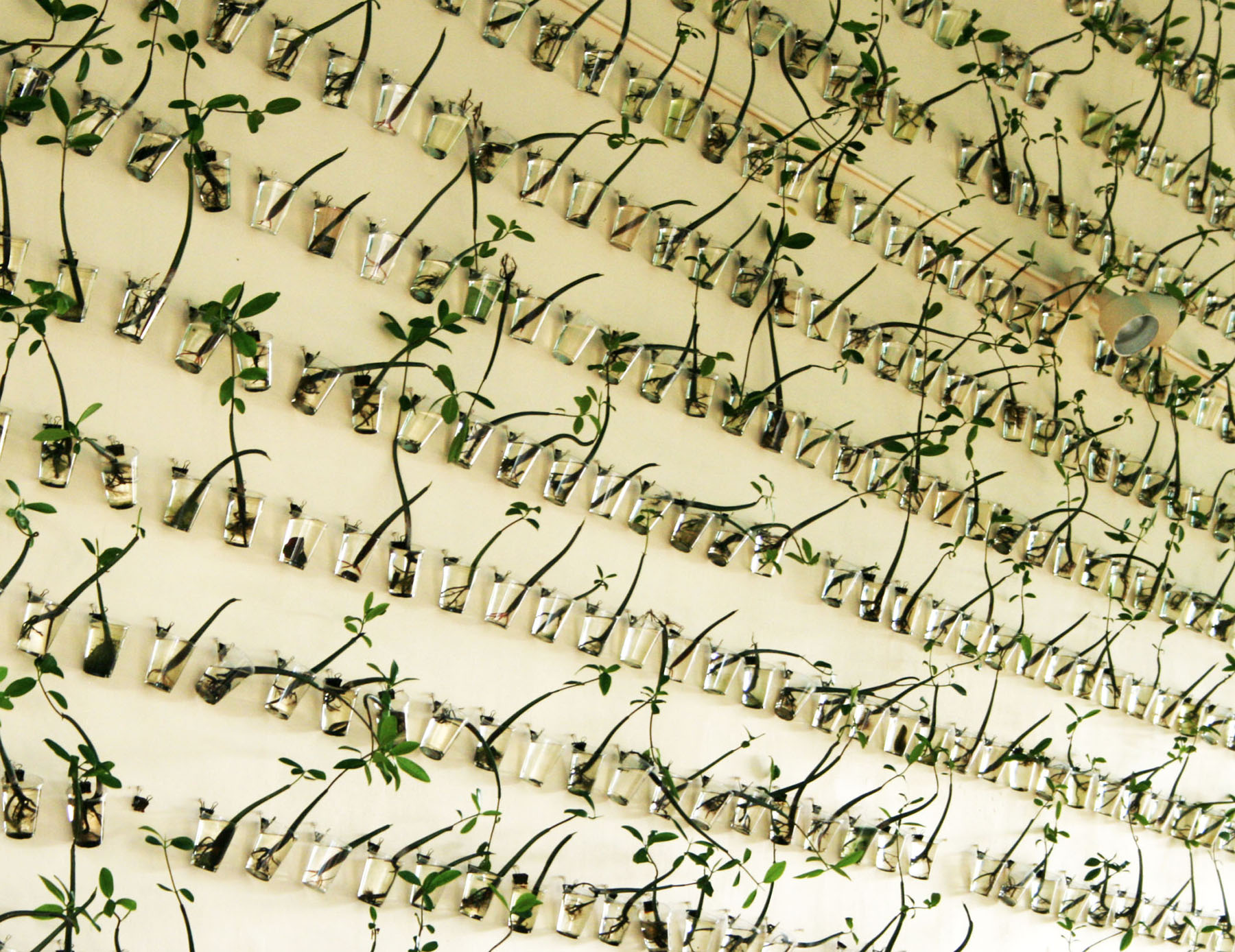

Intersection Painted To Indicate Its Elevation Over Sea Level. ©2021 Xavier Cortada. Photo courtesy of the artist.

For even broader visibility, Cortada approached 4 area schools, soliciting help in enlisting student volunteers to paint roadway intersections with similar elevation markers. In each school, Cortada met with a class (or, in one case, an auditorium full of students) to explain the project. He also met with the art teacher to coordinate the distribution of supplies, devise a suitable painting schedule, and define the project location. (Each school was responsible for 1 intersection.) The students did much of the design work (e.g., creating stencils) in school. Then one to two dozen students showed up weekly at each designated intersection during a 4-week period to complete the “Elevation Drive” paintings on the asphalt.

Cortada also asked residents to join the nation’s first Underwater Homeowners’ Association (HOA), which first met on January 9, 2018 and then monthly at the Pinecrest Gardens’ Hibiscus Gallery for problem-solving discussions about sea level rise. He aimed to provide a discussion forum that sidestepped political divisions. Members of the Association could introduce themselves as “I’m at 4” or “I’m at 10,” finding common ground on the basis of their property elevation, regardless of their political party affiliation.

Progress to date: The project generated widespread interest:

- Based on the initial success in Pinecrest, Cortada immediately expanded the project countywide.

- Over 3,500 yard signs were distributed. Dozens more were painted by participants.

- Volunteer students completed all 4 highway intersection paintings.

- The Underwater HOA has 250 members and has held 25 monthly meetings. (The group continued meeting during the pandemic by Zoom.)

- Underwater HOA members have brought concerns raised during their meetings to existing, traditional homeowners’ associations, creating a secondary audience for climate discussions.

- While the project focuses on Miami-Dade County and its institutions and residents, the universality of its theme and methodology have drawn recognition from media across the globe, including the New York Times, Washington Post, BBC, CNN, Associated Press, NPR, Forbes, Miami Herald and WLRN, among others.