James Balog, Redbud tree in spring bloom, Maggie Valley, NC, April 2001. Photograph. ©2001 James Balog Photography/Earth Vision Institute. Courtesy of the artist.

Few things are as spectacular as a redbud tree in full spring bloom. Showy pink or reddish-purple blossoms adorn graceful branches. As the seasons progress, heart-shaped leaves emerge – reddish at first, dark green in summer and canary yellow in autumn.

Redbuds are integral to American history. Native Americans boiled the bark for medicinal uses and ate the flowers raw or fried. George Washington was also fond of this early spring bloomer, transplanting many to his Mount Vernon gardens.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

James Balog, Eastern White Pine, Lenox, Massachusetts, October 2002. Photograph ©2002 James Balog Photography/Earth Vision Institute. Courtesy of the artist.

Eastern white pines are the tallest conifers native to eastern North America – Pennsylvania’s Cook Forest boasts specimens over 150’ high.

These magnificent trees release aromatic essential oils called phytoncides. Their antibacterial and antifungal components ward off attacking insects and may even benefit human immune systems. Recent research shows spending time in forests can reduce stress, lower blood pressure, and improve concentration – effects that may be due to phytoncides.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Dudley Edmondson, Fall Color on St. Louis River (1998). Photograph. ©Dudley Edmondson. Courtesy of the artist.

An array of deciduous trees close out the growing season in spectacular color.

Brilliant oranges and reds emerge as trees recall the green chlorophyll in their leaves for winter storage in trunks and roots. Soon the trees will discard their leaves, shrinking their surface area to reduce exposure to winter’s strong winds and heavy snows.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Dudley Edmondson, Yosemite High (2005). Photograph. ©Dudley Edmondson. Courtesy of the artist.

The National Park Service has dubbed Yosemite “the meeting place of trees.” An abrupt 13,000-foot rise in elevation accommodates a diversity of climates with distinctive foliage. Drought-resistant trees prefer the dry lower reaches; cold-hardy evergreens edge the timberline.

For tree-lovers, the view from any peak presents a feast for the eyes. Racing to beat sunset, Edmondson captures a high country view in the day’s waning light.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Dudley Edmondson, Florida Sunset (2010). Photograph. ©Dudley Edmondson. Courtesy of the artist.

Trees line the waterway bringing drinking water from Lake Okeechobee to West Palm Beach, Florida. Their leaves are hard at work absorbing carbon dioxide, a major contributor to global warming. They also give off cooling water vapor, which blows inland, reducing droughts. And they soften the impact of heavy rains so soils can soak up rainwater for use and future release.

Tree roots help too, stabilizing stream banks and filtering runoff for cleaner drinking water.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Maya Lin, Ghost Forest, Preparatory sketch for site-specific installation for Madison Square Park opening in 2021 (2019). ©Maya Lin Studio. Courtesy of the artist, Pace Gallery, and Madison Square Park Conservancy.

A grove of spectral trees towers over Manhattan’s Madison Square Park in Maya Lin’s preparatory sketch for a site-specific installation. The trees (25 to 40 ft. high) are cedars from the nearby New Jersey Pine Barrens, destroyed by saltwater inundation during Hurricane Sandy.

The installation’s title – “ghost forests” – refers to the vast tracts of forest decimated by the sea level rise and saltwater infiltration that accompany climate change. Lin’s installation is a call to action – a grave reminder of the consequences of inaction.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Lee Goodwin, James River, June Evening, 2013. Digital photograph printed on archival paper. ©Lee Goodwin 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

High water laps at the base of shoreline trees on Virginia’s lower James River. Low-lying land in the “Tidewater,” the Atlantic coastal plain from North Carolina to Delaware, makes the region vulnerable to sea level rise, flooding and storm surges.

Goodwin warns: “The landscape we see today may not be there for our children, or even for ourselves in the coming decades.” He intends to show “what we have to lose” if climate change swallows our shorelines.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Alexis Rockman, Grey Twister, Green Field from Weather Drawings (2005). Oil on gessoed paper. Dimensions: 38.75” x 59”. ©2005 Alexis Rockman. Courtesy of the artist.

A twister bears down on a vibrant green field, spelling trouble for surrounding trees. Trees are particularly vulnerable to tornadoes in summer. Leafy branches offer more resistance to violent winds capable of snapping off crowns and splintering trunks.

Scientists report the behavior of tornadoes in the U.S. is changing, perhaps due to climate change. More study is needed to assess how climate change will affect the direction and magnitude of future tornadoes.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Peter Handler, Drunken Forest from the Canaries in the Coal Mine series (2016). Walnut, birch, anodized aluminum. Dimensions: 24” d x 50” l x 44” h. ©Handler Studio 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

As temperatures rise, the frozen ground or “permafrost” underlying 85% of Alaska is thawing, destabilizing soils and causing trees to lean or fall. “Drunken” forests are not new to Alaska, but the current speed and scale of dislocation is new – and ominous.

Handler’s imbalanced trees stand atop a woefully frail-legged platform. The aesthetic discord invites us to ponder: Alaska’s forests, part of the planet’s “lungs,” absorb carbon dioxide and release oxygen as they photosynthesize. What will happen if large forest tracts disappear?

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Peter Handler, Firefighters at Aggie Creek, Alaska (2015). Photograph. ©Handler Studio 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Alaskan wildfires are more frequent and immense now. Summer 2015 set a near record: nearly 5,000,000 acres burned.

Handler’s photograph reveals the scale, intensity, and duration of a single wildfire: “This fire was still smoldering almost a week after it had peaked. Smoke had been so thick that outdoor activities were cancelled in Fairbanks, about 45 miles away. When this photo was taken, flames had mostly burned out, but firefighters still needed to eliminate smoldering underground fire pockets that could flare anew.”

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Eric Serritella, Whisper & Wander (2016). Ceramic. Dimensions: 32” h x 56” w x 32” d. ©2016 Eric Serritella. Photographer: Jason Dowdle. Courtesy of the artist.

Serritella’s sculpture captures the interaction between two charred trees struggling to survive the aftermath of a wildfire. Whisper’s quiet negative space hints at remaining life. Wander seeks a gap in the canopy for more light to grow.

Their fates are intertwined because survival depends on the health of the forest ecosystem. Whisper and Wander can support and nourish each other through a “wood wide web” of interconnected roots and fungi to assure mutual survival.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Alexis Rockman, Cascade (2015). Oil and alkyd on wood panel. Dimensions: 72” x 144”. ©2015 Alexis Rockman. Courtesy of the artist.

Rockman’s mural-sized painting explores the Great Lakes’ past, present and future – from the last ice age to colonial era virgin forests to deforestation from agricultural, industrial and urban development.

Rockman asks: “The lakes contain 20% of Earth’s and 95% of our nation’s surface freshwater. They are ‘ground zero’ for the future when freshwater will be Earth’s most valuable asset. Yet they are neglected, exploited, and further stressed by climate change. Can we face the reality of our actions and the consequences of complacency?”

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Edward Burtynsky. Clearcut #1, Palm Oil Plantation, Borneo, Malaysia, 2016 from the Anthropocene series. Photograph. ©Edward Burtynsky. Courtesy of Weinstein Hammons Gallery, Minneapolis / Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto.

Every year, humans eliminate roughly 18.7 million acres of forestland, mainly for agriculture. Palm oil production drives much of this land conversion, generating cheap vegetable oil for cooking and biofuels. Spurred by soaring world demand, Indonesia is sacrificing large swaths of Borneo’s tropical forests to increased palm oil production.

Eliminating forests removes carbon capture opportunities, increases erosion (to the detriment of soils and waterways), and deprives the ecosystem of the forests’ drought-reducing functions. Burtynsky aims to capture the scale of deforestation and its impacts on people, animals and ecosystems.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Edward Burtynsky, Sawmills #1, Lagos, Nigeria, 2016 from the Anthropocene series. Photograph. ©Edward Burtynsky. Courtesy of Weinstein Hammons Gallery, Minneapolis / Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto.

Nigeria is a global hotspot for pristine forest loss. In previously unspoiled rainforests, loggers cut down trees, dumping them in the river to float downstream to the sawmills of Lagos. There, logs are resized into lumber for firewood and furniture.

The process despoils the environment in both locations. Rainforest destruction erodes soils, pollutes streams, and turns fertile land to desert. Milling generates sawdust and muddies Lagos’ waterways. Burtynsky makes the devastation visible, spurring us to question how we manage earth’s resources.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Judy Chicago, Harvested from The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction (2016). Kiln-fired glass paint on black glass. Dimensions: 18 x 12 in. (45.72 x 30.48 cm.). © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo © Donald Woodman/ARS, NY. Courtesy of the artist; Salon 94, New York; and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco.

Chicago sounds a clarion call to save a valuable medicinal plant: “A species of Himalayan yew tree is being pushed to the brink of extinction by overharvesting for medicinal use. The harvesting of the bark kills the tree. It takes SIX TREES to create ONE DOSE OF MEDICINE. Is it too much to ask that we plunder the natural world in a SUSTAINABLE WAY?”

Conservation measures could raise local awareness of this plant’s importance, end illegal cutting, sustainably manage harvesting, and embrace reforestation.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

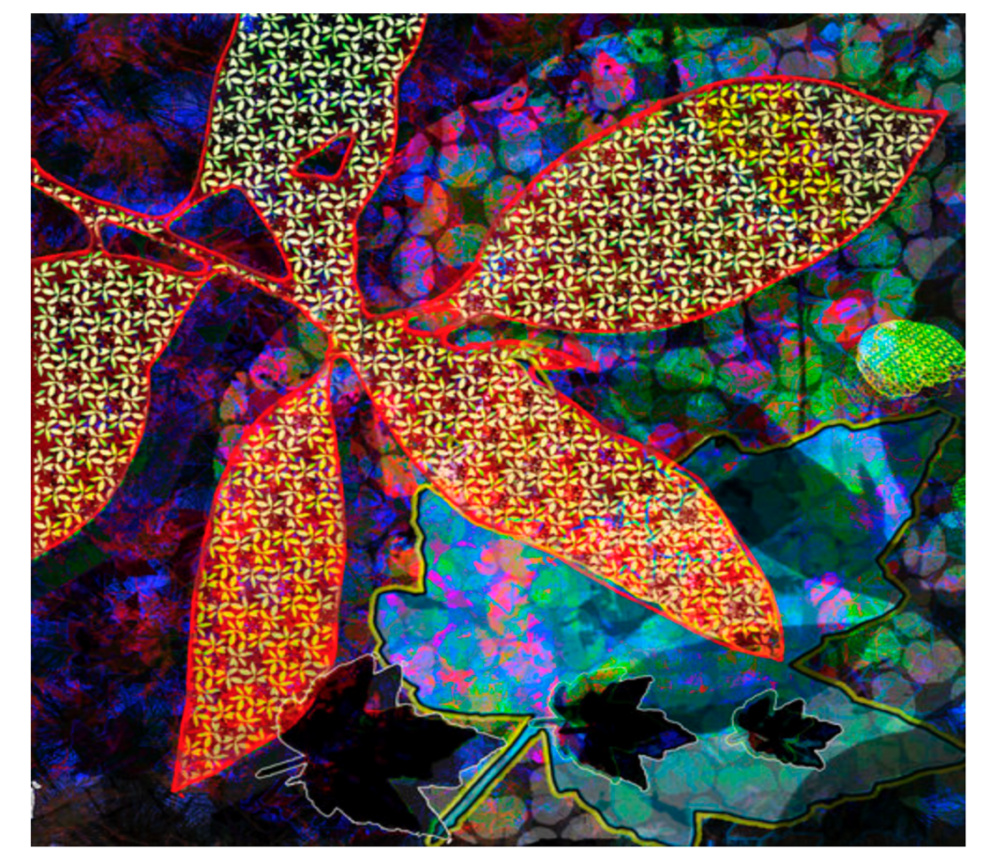

Jiyoung Chung, Whisper-Romance – Contented (2013). One-of-a-kind joomchi with paper yarn. Dimensions: 35” x 23.5”. © 2013 Jiyoung Chung. Courtesy of the artist.

Chung is a master of joomchi, the ancient Korean, environmentally sustainable art of handcrafting paper from water and the inner bark of pruned mulberry branches.

Her profound insight: “We have “horse whisperers” and “dog whisperers,” but we need “human whisperers” to heal what has been broken in our relationship to ourselves, to nature and to God. The holes, layers and free mounting of my work represent these conversations, the whispers and the breath between them.”

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

![Claire Kelly, Parallax: Busy Forest (2019). [Parallax: The effect whereby the position or direction of an object appears to differ when viewed from different positions.] Glass: Blown, sculpted, and assembled. Dimensions: 15 ¼" x 16" x 36.” © Claire Kelly Glass. Courtesy of the artist. Claire Kelly, Parallax: Busy Forest (2019). [Parallax: The effect whereby the position or direction of an object appears to differ when viewed from different positions.] Glass: Blown, sculpted, and assembled. Dimensions: 15 ¼" x 16" x 36.” © Claire Kelly Glass. Courtesy of the artist. Kelly’s playful glass sculptures invite us to enter and explore the worlds where animals dwell. She aims to stir our curiosity about the animals within this intimate kingdom: what is their role in, and value to, the larger ecosystem? What threats await them? And, most importantly, what do they see when they look back at us? Her work presents “a gentle mirror” for examining how our decisions affect our environment.](https://www.honoringthefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Kelly_Claire_Parallax_Busy-Forest-1.jpeg)

Claire Kelly, Parallax: Busy Forest (2019). [Parallax: The effect whereby the position or direction of an object appears to differ when viewed from different positions.] Glass: Blown, sculpted, and assembled. Dimensions: 15 ¼” x 16″ x 36.” © Claire Kelly Glass. Courtesy of the artist.

Kelly’s playful glass sculptures invite us to enter and explore the worlds where animals dwell.

She aims to stir our curiosity about the animals within this intimate kingdom: what is their role in, and value to, the larger ecosystem? What threats await them? And, most importantly, what do they see when they look back at us?

Her work presents “a gentle mirror” for examining how our decisions affect our environment.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

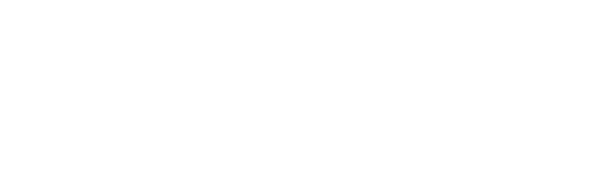

Nancy Cohen, Settling In (2019). Paper pulp, ink and handmade paper. Dimensions: 77″ x 73″. ©Nancy Cohen 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

The day Cohen settled into a studio in a neglected residential area, she found a welcome surprise. Some kind soul had removed a dilapidated building in the adjacent lot, revealing a view of a majestic, 7-story high tree outside her window.

Marveling at the pollution and neglect the tree must have endured to survive, Cohen created Settling In to pay homage to the tree’s resilience and to remind us to notice and treasure nature’s wonders in our midst.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Nancy Cohen, Scrim (2019). Paper pulp, ink and handmade paper. Dimensions: 52” x 45”. ©Nancy Cohen 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Kathryn Markel Fine Arts.

Cohen offers two views of mangroves: the bark supporting their towering heights and their tangled roots – habitat for oysters, shrimp and crabs. Hardy and ingenious, mangroves thrive where salt, temperature and water levels vary with the tide. Stilt-like roots prop mangrove breathing pores above muddy water and form massive, coast-protecting barriers against strong waves.

Scrim is both a tribute to an eco-tourism paradise and a plea for humans to respect this vulnerable ecology.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Sheila Ransom, Basket given to Pope Benedict XVI upon the canonization of Mohawk Kateri Tekakwitha (2012). Black ash and sweetgrass. ©Sheila Ransom, 2012. Courtesy of the artist.

Basketmaking is a cherished Akwesasne Mohawk skill, passed from generation to generation to give thanks for creation and celebrate tribal values. Today, black ash trees for basketmaking are scarce – victims of pollution, overharvesting, and habitat destruction. Climate warming favors a new menace: the tree-devouring emerald ash borer.

The resilient Akwesasne are saving seeds to regenerate ash stands as they search for alternative raw materials. Ransom explains: “Because it takes 40-50 years for ash trees to grow to a good size, only future generations will see the fruits of our labor. We persevere because it is our responsibility to preserve this gift of creation for future generations.”

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

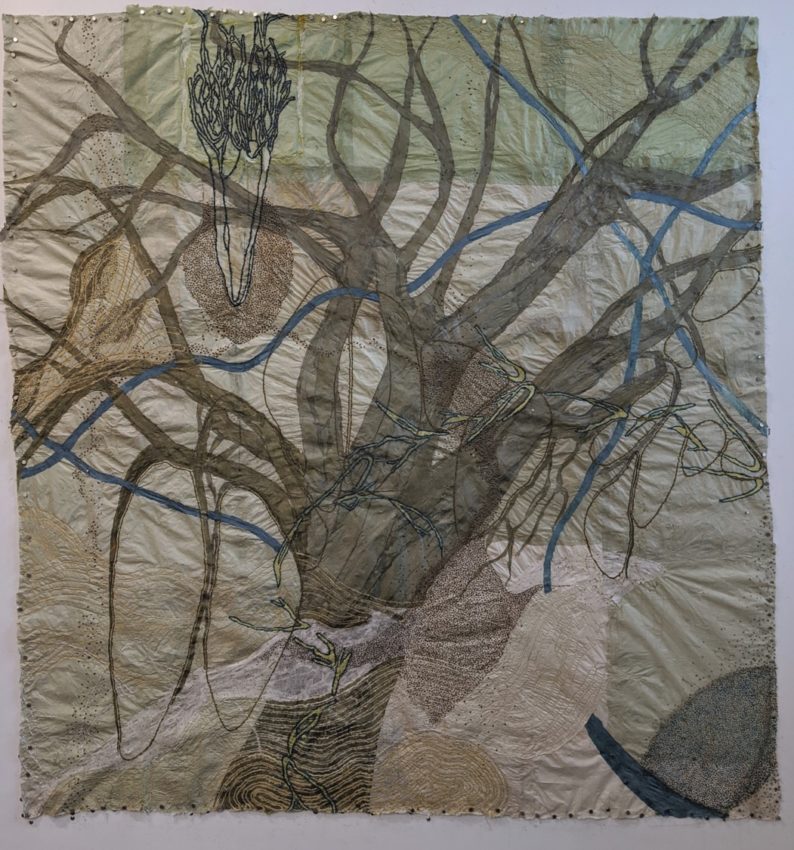

Xavier Cortada, Growing our Native Canopy 1 (Bald Cypress, Red Cedar, Slash Pine) (detail) (2009). Pigment Print on Somerset Velvet, Edition 1 of 1. Dimensions: 24″ x 84.″ ©2009 Xavier Cortada. Courtesy of the artist.

Cortada created this and the digital painting which follows to celebrate the planting of 750 native trees in Pinellas County, Florida. The planting grew out of Cortada’s pioneering “Reclamation Project” – an initiative to restore Florida’s coastal and upland forests.

Four principles guide this project: Set goals informed by scientific findings. Foster collaboration across disciplines – artist to scientist to public official and beyond. Encourage communities to become directly involved in solving environmental problems. Fuse artistic creation with environmental stewardship at every stage.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

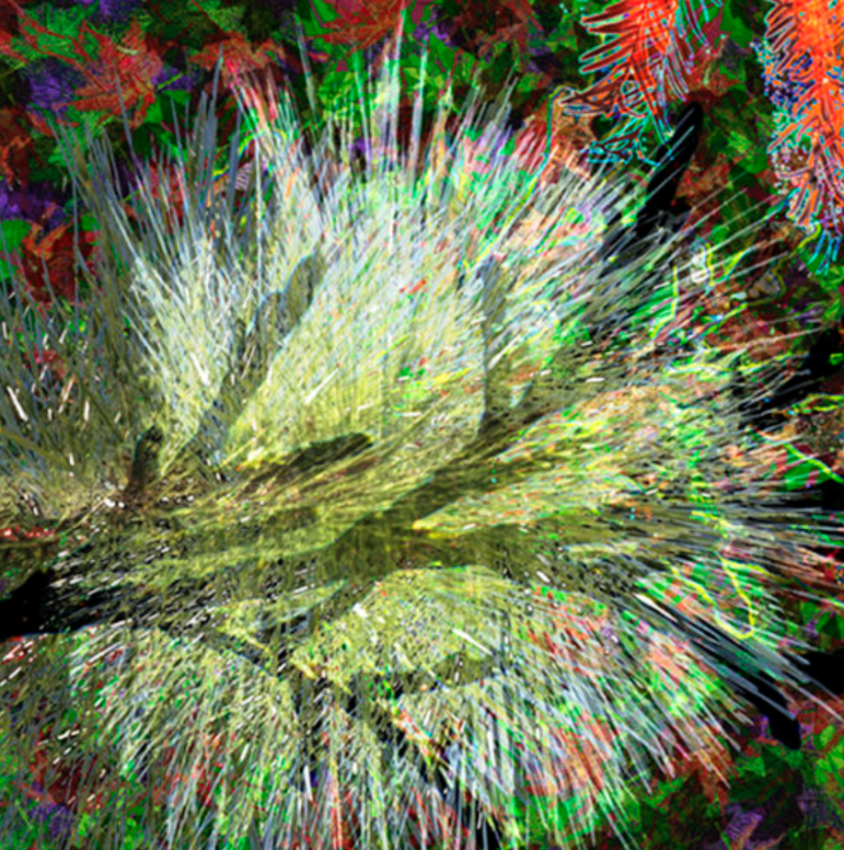

Xavier Cortada, Growing our Native Canopy 2 (Green Buttonwood, Red Maple, Seagrape) (detail) (2009). Pigment Print on Somerset Velvet, Edition 1 of 1 (2009). Dimensions: 24″ x 84″. ©2009 Xavier Cortada. Courtesy of the artist.

This and the preceding digital painting, both part of Cortada’s Reclamation Project, invite Floridians to reimagine – and act creatively to restore – “what our community looked like before all the concrete was poured.”

The project encourages Floridians to plant a native sapling in their front yard alongside a flag announcing: “I hereby reclaim this land for nature.” The flags serve as catalysts to engage neighbors in conversation about restoring native habitats – one of many creative project approaches to community engagement.

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Eric Serritella, Sassy Birch Teapot (2009). Ceramic. Dimensions: 16” h x 16” w x 8” d. ©2009 Eric Serritella. Courtesy of the artist.

Serritella’s Sassy Birch packs three surprises into one tiny sculpture. Its tattered bark is carved from clay. The sculpture disguises a functioning teapot. And it seems human – leaning towards us, resilient, imploring.

Having roused our curiosity, Serritella challenges: “I strive to show nature’s tenacity. She triumphs, maintaining her splendor despite our disregard. My hope is that at least some will acquire new appreciation – and choose to walk with softer steps.”

Use arrow above to view next image.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.

Resource Directory

The following exhibition cosponsors offer volunteers opportunities to help plant and care for trees and educate others about the importance of trees to our future. Please consider lending them a hand!

ArizonaAt 7,150 feet in elevation, The Arboretum at Flagstaff offers unique, spectacular views of the San Francisco Peaks, miles of trails upon which to stroll, and opportunities to learn about our native plants. We aim to increase understanding, appreciation and conservation of the Colorado Plateau’s native plants and plant communities. ConnecticutThe Bartlett Arboretum & Gardens is one of Fairfield County’s leading botanical and horticultural education resources featuring 93 acres of open, green space located on the historical property of well-known arborist Dr. Francis A. Bartlett. Edgerton Park Conservancy is an all-volunteer, membership organization dedicated to sustaining New Haven’s Edgerton Park. We support the preservation, restoration and enhancement of this public park, sponsor horticultural education and programming, and promote the park as a place for public use and enjoyment. DelawareDelaware Center for Horticulture’s work strengthens the social fabric and builds more livable cities by enhancing their environmental, economic, and aesthetic qualities. We create neighborhoods that are healthier, more attractive, and more ecologically sustainable. IndianaGabis Arboretum at Purdue Northwest serves as a living laboratory for education, research, conservation and engagement with the natural environment. The arboretum is home to many rare plants and animal species and has restored the native prairies, woodlands and wetlands of the northwest Indiana landscape. |

KentuckyThe Arboretum, State Botanical Garden of Kentucky is a 100-acre greenspace on the campus of the University of Kentucky in the heart of Lexington, Kentucky. We showcase Kentucky landscapes and serve as a resource center for environmental and horticultural education, research and conservation. MarylandEach year, Audubon Naturalist Society provides more than 28,000 children and adults across the Washington DC area with opportunities to connect to the natural world and learn to appreciate and protect nature through environmental conservation, restoration, and education programs. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation is the largest independent conservation organization dedicated solely to saving the Bay. Through education, advocacy, restoration and litigation, we fight for effective, science-based solutions to the pollution degrading the Chesapeake’s six-state, 64,000-square-mile watershed. PennsylvaniaThe Keystone Ten Million Trees Partnership is a collaborative effort by national, regional, state, and local agencies, conservation organizations, outdoors enthusiasts, businesses, and citizens, aimed at facilitating the planting of 10 million new trees in priority landscapes in Pennsylvania by the end of 2025. The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society is a nonprofit organization focused on using horticulture to advance health and well-being. PHS Tree Tenders® works to increase the number of trees in neighborhoods throughout Philadelphia, prioritizing communities with tree coverage well below the citywide goal of 30% of open space. |

Thank you for visiting our exhibition!

(Click on right arrow to start again)