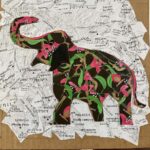

Carolyn Peirce, Giant Panda, Recycled paper collage ©2020 Carolyn Peirce. Courtesy of the artist.

Giant Panda

Status: vulnerable

Giant pandas once roamed much of China, but now are confined to the bamboo forests of its mountainous southwest. Today only 500 -1,000 mature giant pandas remain.

Pandas thrive almost entirely on bamboo leaves, shoots and stems, eating 25-30 pounds a day. As humans clear forests for agriculture, mining, and development, pandas are confined to isolated forest fragments, reducing access to multiple bamboo species (with varying nutritional values) and to different elevations (with higher seasonal bamboo concentrations).

Climate change may decrease the amount – or alter the type – of bamboo in each forest fragment. Climate-related droughts and floods may also increase demand for cropland. Habitat protective measures can strengthen pandas’ ability to survive these additional threats.

Carolyn Peirce, Siberian Tiger, Recycled paper collage ©2020 Carolyn Peirce. Courtesy of the artist.

Siberian Tiger

Status: Endangered

Siberian or Amur tigers, the world’s biggest “cats,” had almost disappeared by the 1930s, dwindling to only 20-30 individuals. Then in 1935, Russia created a 900,000+ acre reserve for their protection. This and other conservation measures helped populations rebound. Now, an estimated 500 Siberian tigers remain in the wild – 95% of them in far eastern Russia.

Poaching for illegal trade in tiger skins, bones, meat and tonics remains the biggest threat to survival, followed by habitat loss from converting forests to farmland, logging, and other human encroachment.

In 2010, 13 countries with free-roaming tigers pledged to work together to preserve habitats and end poaching, with the goal of doubling the world’s tiger population by 2022.

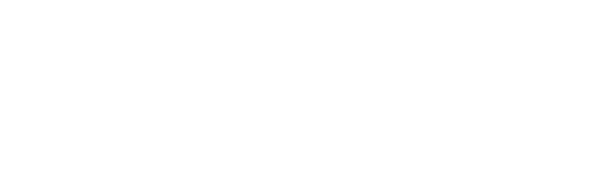

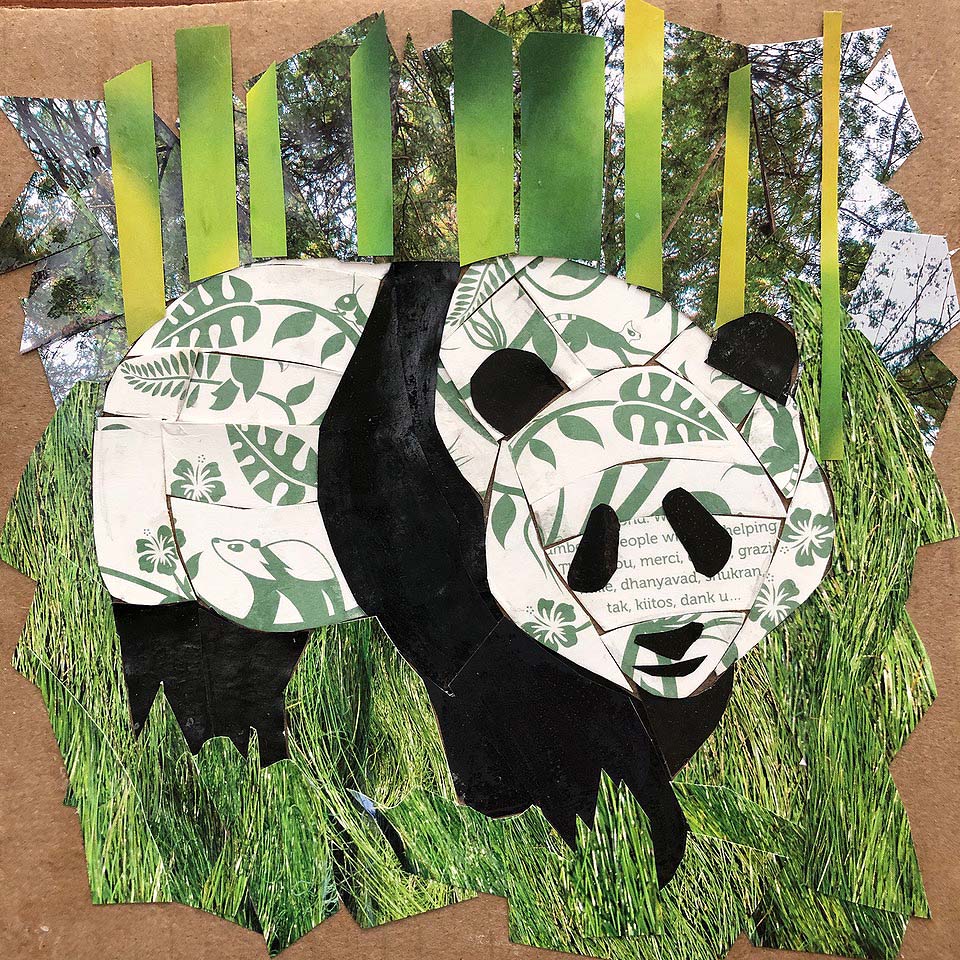

Carolyn Peirce, Amur Leopard, Recycled paper collage ©2020 Carolyn Peirce. Courtesy of the artist.

Amur Leopard

Status: Critically endangered

Amur Leopards (also called Far East, Manchurian, or Korean leopards) are amazingly strong: they can tackle prey 10 times their weight. Considered the best stalkers and climbers of the “big cats,” they are also the most vulnerable: less than 90 remain in the wild.

As humans felled temperate forests in Far Eastern Russia, northern China and Korea, leopards and their prey (roe and Sika deer and badgers) dwindled. Poachers also took a toll, valuing the leopard’s soft, thick coat for its beauty and the bones for traditional Asian medical treatments.

About 200 Amur leopards survive in captivity. Careful breeding may save them from extinction.

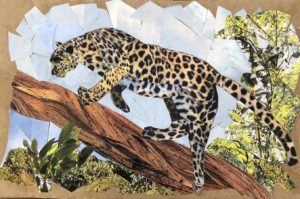

Carolyn Peirce, Ring-tailed Lemur, Recycled paper collage ©2020 Carolyn Peirce. Courtesy of the artist.

Ring-tailed Lemur

Status: Endangered

The ring-tailed lemur is extraordinarily versatile, inhabiting caves, shrubland, forests and rocky peaks. It eats a varied diet, endures extreme temperature swings, and can be active day or night.

Yet despite remarkable adaptability, the lemur is endangered – its fate tied to that of Madagascar, its only home. By now, Madagascar has lost 90% of its original forest due to slash-and-burn agriculture, over-grazing, logging and human encroachment. Lemurs – confined to small, isolated forest fragments – are further threatened by hunting and illegal pet traders.

Climate models predict that intense droughts, cyclones, storms, and floods will destroy 63% of remaining lemur habitat in the absence of successful human efforts to protect these wild places.

Carolyn Peirce, Panamanian Golden Frog, Recycled paper collage ©2020 Carolyn Peirce. Courtesy of the artist.

Panamanian Golden Frog

Status: Critically endangered (possibly extinct in the wild)

Panama’s golden frog is an important national symbol, celebrated with fanfare on National Golden Frog Day every August 14.

Once common in Panama’s tropical forests and popular as pets, golden frogs were over-collected to near extinction. Agriculture and development encroached on their forest habitats; road-building sediment clogged forest streams. Beleaguered frogs proved no match for the stresses of climate change and the highly infectious chytrid fungus, which caused massive worldwide amphibian die-offs.

Golden frogs are now possibly extinct in the wild. The last wild frog was seen in 2009. Successful captive-breeding programs hold promise for reintroducing golden frogs to the wild if we preserve at least some former habitats.

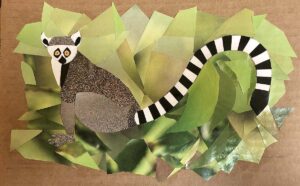

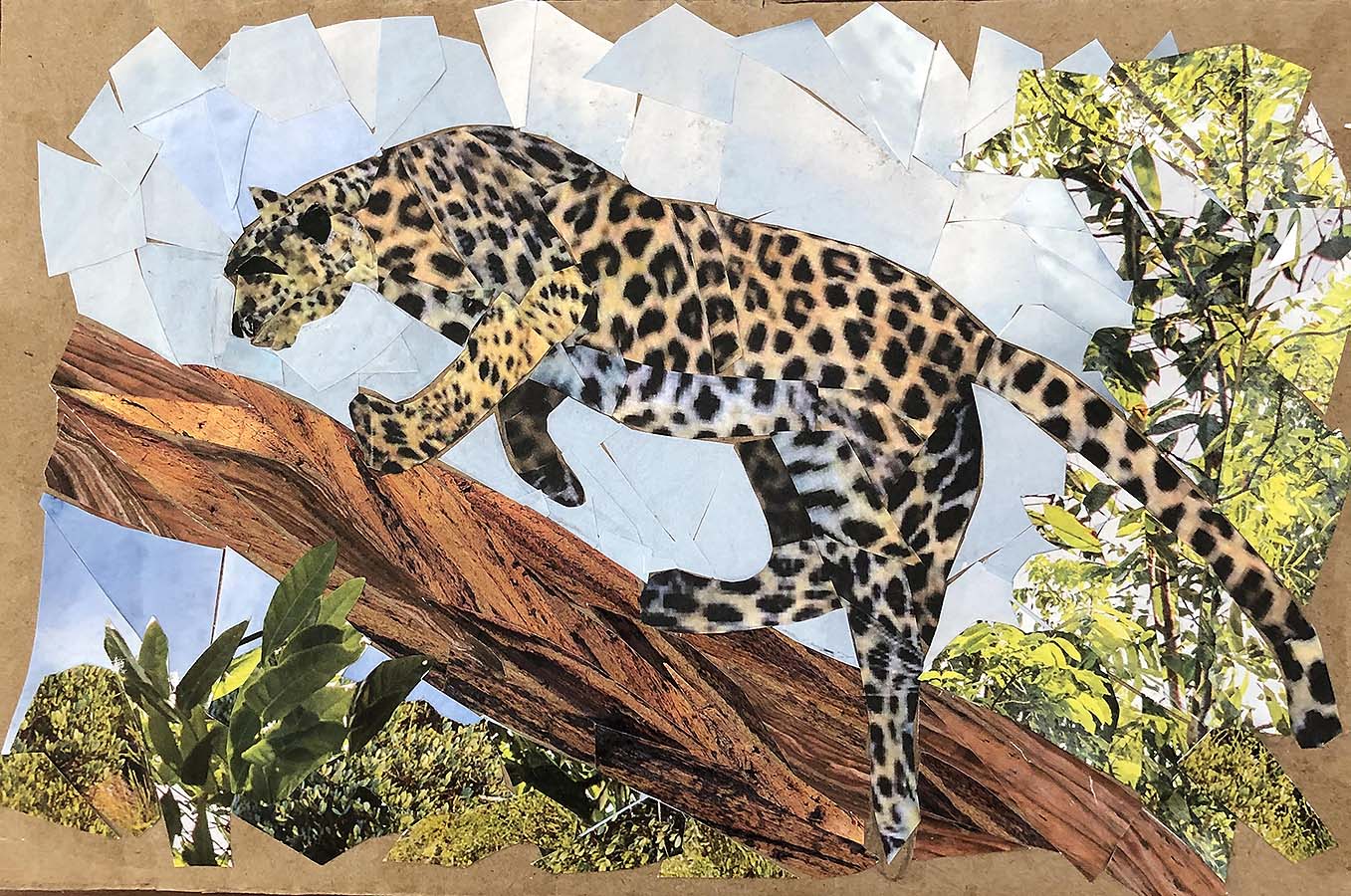

Carolyn Peirce, Hawksbill Turtle, Recycled paper collage ©2020 Carolyn Peirce. Courtesy of the artist.

Hawksbill Turtle

Status: Critically endangered

Bred on sandy beaches, Hawksbill turtle hatchlings embark on long, imperiled journeys across tropical seas.

The turtles face multiple threats. Though international trade in tortoiseshells for jewelry and ornaments is now largely prohibited, illegal trading persists. Turtles are slaughtered for meat and shark bait, entangled in fishing nets and gear, and swarmed by marine debris, which, if mistaken for food and ingested, can injure, starve and kill. Oil slicks damage their ability to breathe, feed, swim and reproduce. Climate change endangers coral reefs on which they forage. Beachfront developments and refineries destroy their nesting sites. Humans consume their eggs.

Yet protected populations have stabilized or increased, proving turtles can still be saved.

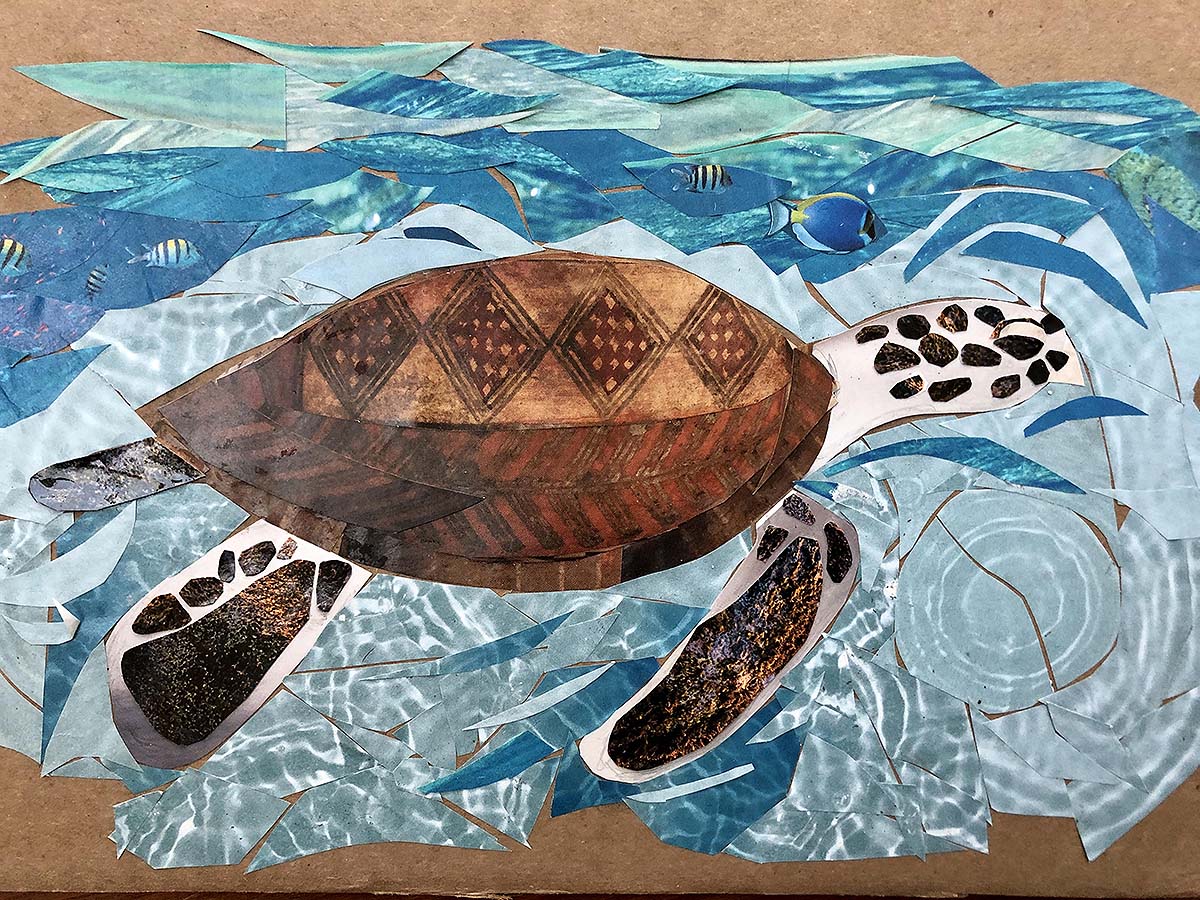

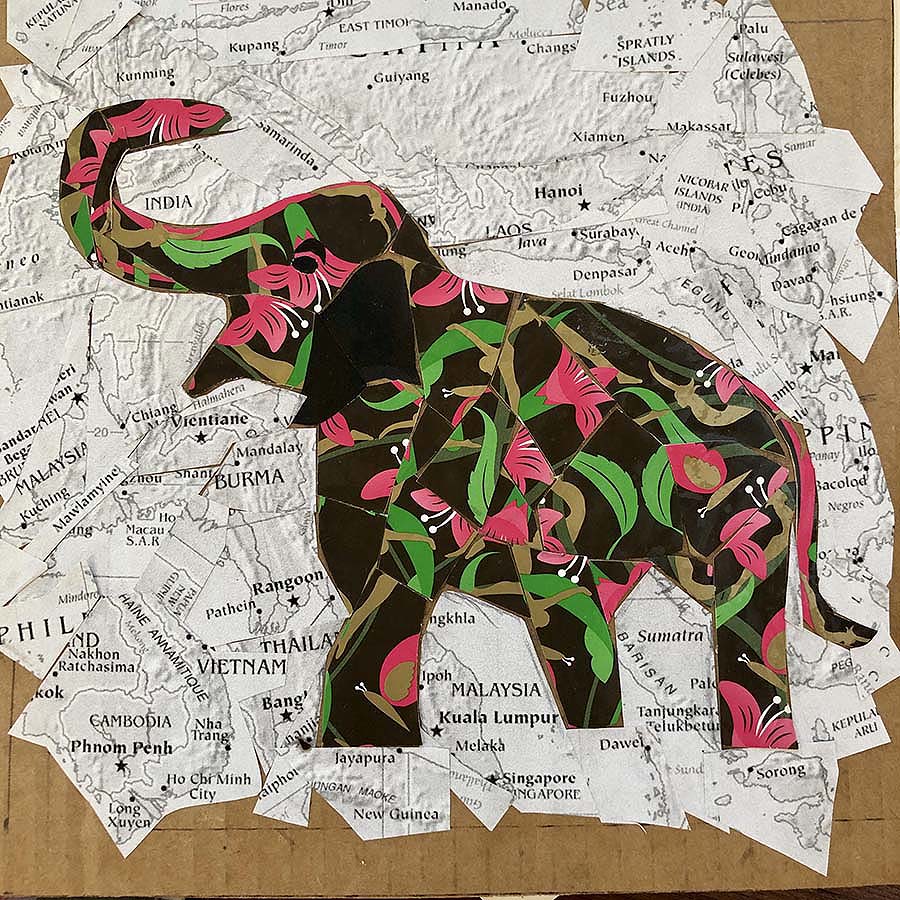

Carolyn Peirce, Asian Elephant, Recycled paper collage ©2020 Carolyn Peirce. Courtesy of the artist.

Asian Elephant

Status: Endangered

A male Asian elephant needs about 330 pounds of food per day to maintain its 5-ton weight. Foraging for that much food requires large amounts of territory – more than most other land-based mammals need.

But Asian elephants inhabit grassland and forests in densely populated India and southeast Asia where expanding human populations are drastically reducing elephant habitat. What remains are often small, isolated forest fragments, crisscrossed by roads and human clearings.

Annually, hundreds of elephants are killed when they wander off these plots and eat or trample crops. Poachers seize many more for meat, hides, and ivory tusks. Resolving local human-elephant conflicts is key to elephant survival.

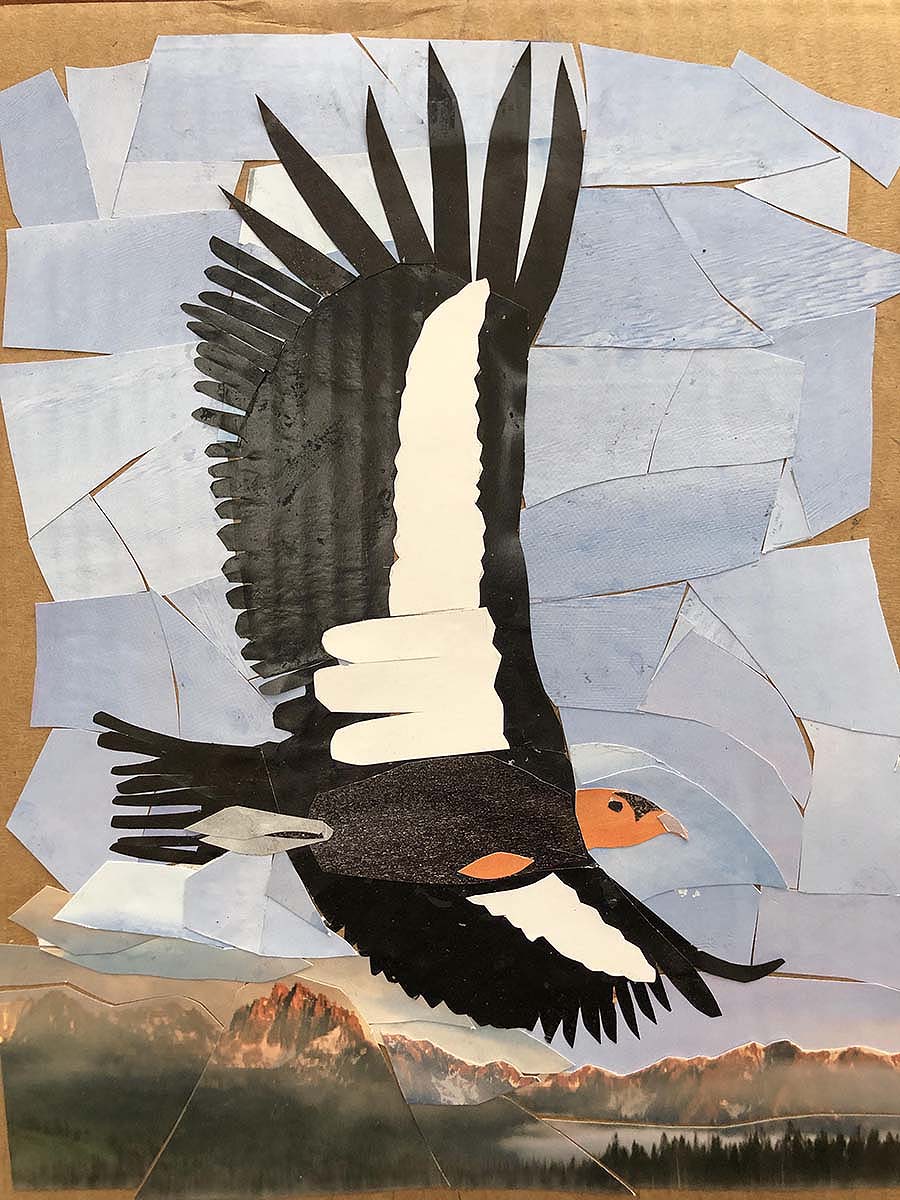

Carolyn Peirce, California Condor, Recycled paper collage ©2020 Carolyn Peirce. Courtesy of the artist.

California Condor

Status: Critically Endangered

California condors are North America’s largest land birds. With an exceptionally long (nearly 10-foot) wing span, condors glide for miles, scavenging for animal carcasses to eat.

Many ingested lead from animals hunted with lead shot. Others were incidentally poisoned when farmers set out contaminated carcasses to exterminate coyotes – or sprayed DDT to eradicate insects. And high concentrations of the now-banned DDT thinned condors’ eggshells, weakening eggs (laid only once every two years).

In 1987, when only 27 condors remained, the U.S. government led efforts to capture all wild condors, breed them in captivity, and reintroduce them to the wild. There are now over 400 condors. Efforts to reduce lead exposure will aid their survival.

Carolyn Peirce, Monarch Butterfly, Recycled paper collage ©2020 Carolyn Peirce. Courtesy of the artist.

Monarch Butterfly

Status: Decision on status due December 2020

With vivid orange wings, black veins, and white spotted margins, monarchs are among earth’s most beautiful pollinators. Impressive travelers, they migrate from Canada and the northern U.S. to winter in Mexico, returning north each spring.

Since the mid 1990s, monarch populations have plummeted more than 80% – victims of extreme weather, herbicides, pesticides, and habitat destruction.

In 2014, environmental organizations – supported by more than half a million people – petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) to protect the monarch from extinction. After initially finding that protection may be warranted under the federal Endangered Species Act, the FWS postponed a final decision until December 2020. The monarch’s fate hangs on the outcome.

Carolyn Peirce, Hawaiian I’iwi, Recycled paper collage ©2020 Carolyn Peirce. Courtesy of the artist.

Hawaiian I’iwi

Status: Vulnerable

The I’iwi is an eye-catching bird, easily spotted in the wild with its brilliant scarlet plumage, sleek black wings and tail, and long, curved, salmon-colored beak. Once plentiful throughout Hawaii, its numbers drastically dwindled in the last 30 years.

Avian malaria is the main culprit, spread by non-native mosquitoes. Until recently, Hawaii’s higher elevation forests were too cold for mosquitoes, affording some safe haven for the remaining I’iwis.

But as climate warms, mosquitoes are creeping upward in elevation, reducing I’iwi habitat. Scientists hope ongoing research can discover effective mosquito controls or identify and help breed birds with tolerance or immunity to avian malaria.

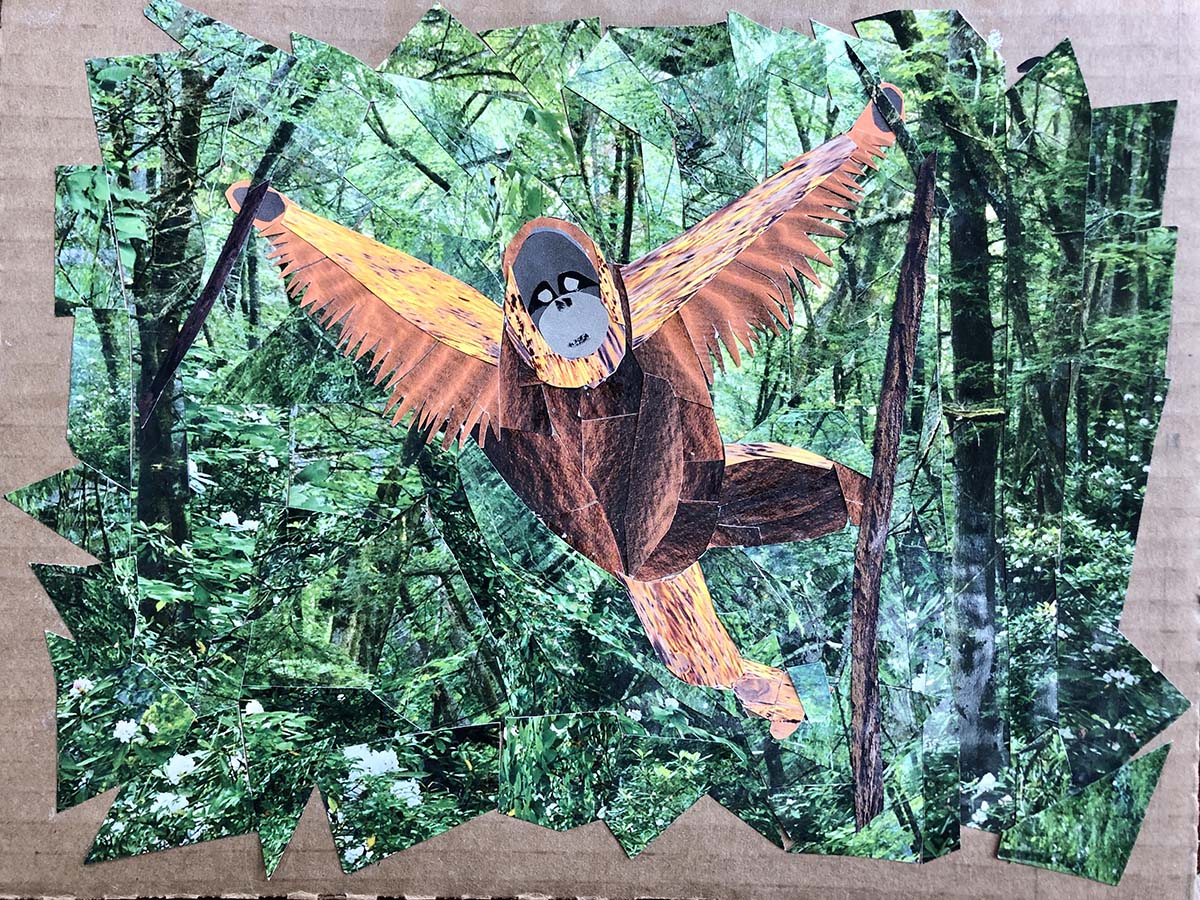

Carolyn Peirce, Sumatran Orangutan, Recycled paper collage ©2020 Carolyn Peirce. Courtesy of the artist.

Sumatran Orangutan

Status: Critically endangered

Sumatran Orangutans are forest dwellers who cling to the tree canopy and rarely set foot on ground. Thousands suffocate from smoke inhalation or are trapped and burned alive when wildfires are set to clear land for palm oil production.

Survivors, crowded into adjacent forest patches where they compete for limited resources, often die of malnutrition and starvation. Logging, poaching and hunting are also threats, as is road building, which fragments forests, inviting further encroachment.

Roughly 14,000 orangutans remain in the wild. Fruit eaters, they help preserve forests by dispersing seeds as they roam. Healthy forests, in turn, preserve water and soil quality and offer long-term, sustainable options for alleviating poverty.

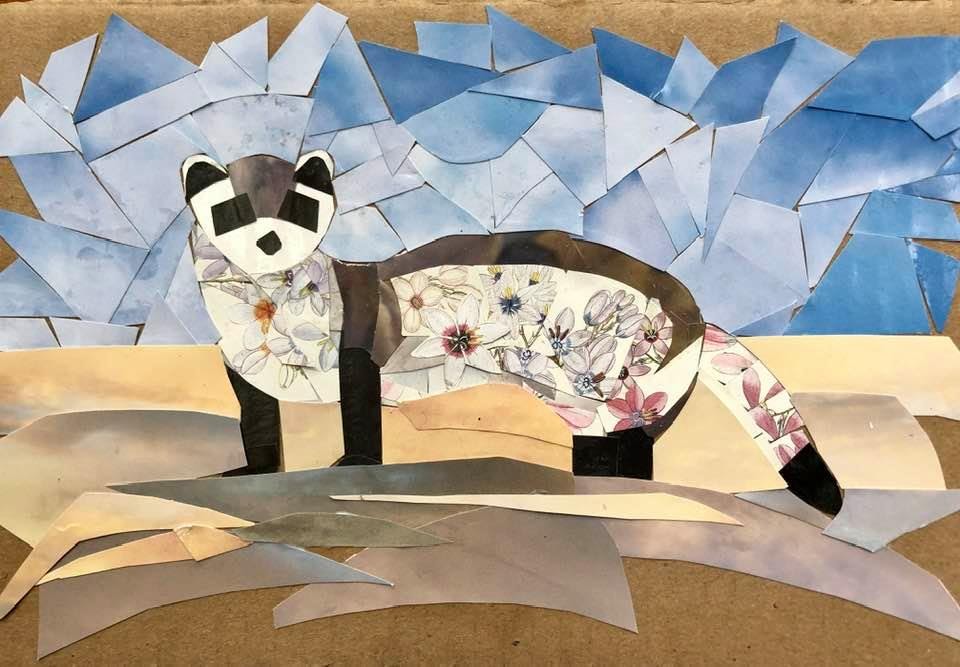

Carolyn Peirce, Black-footed Ferret, Recycled paper collage ©2020 Carolyn Peirce. Courtesy of the artist.

Black-footed Ferret

Status: Endangered

Black-footed ferrets are striking, with long slender bodies, short stout legs, and dramatic dark accents on their faces, legs, and tails.

Ferrets once thrived throughout the west, from Canada to Texas, Arizona and New Mexico, hunting prairie dogs, which comprise 90% of their diet.

Repeated campaigns to exterminate prairie dogs (for digging holes and eating grasses in livestock pastures) impeded ferrets’ hunting – and incidentally poisoned them. Further devastated by disease and loss of 98% of their habitat, ferrets were considered extinct until a dog discovered a small remaining group in 1981. Ferrets’ survival now rests on the success of federal efforts to breed and reintroduce captives to the wild.

Carolyn Peirce, Galapagos Penguin, Recycled paper collage ©2020 Carolyn Peirce. Courtesy of the artist.

Galapagos Penguin

Status: Endangered

Straddling the Equator, Galápagos Penguins are the world’s most northern penguins – and the only penguins living in a tropical environment. Heat-beating strategies are key to their survival.

The penguins typically cool themselves and forage in the archipelago’s cool, nutrient-rich and fish-laden shoreline currents. But frequent El Niño events since the 1970s have warmed ocean waters, driven fish away, and decimated penguin populations. Scientists estimate that only 1,200 penguins remain. That number is expected to decline even further as climate change increases the frequency and severity of El Niño events.

Conservation programs are underway to protect penguins, restrict access to breeding sites, and maintain “no fishing” zones. Program implementation is critical.

All materials in this exhibition are copyrighted. ©Open Space Institute, Inc./Honoring the Future 2020. Please respect this copyright and those of the artists who have generously contributed images to this exhibition.